Volume 12 - Year 2025 - Pages 473-481

DOI: 10.11159/jffhmt.2025.047

Optimization of Additive Manufacturing Processes for Vehicle License Plates via Discrete Event Simulation and Cost Analysis

Paola Michelle Pascua Cantarero1, Gustavo Rosales2, Alejandra Sanchez3

1-3Universidad Tecnológica Centroamericana (UNITEC)

Boulevard Kennedy, V-782, frente a Residencial Honduras, Tegucigalpa, Honduras

paomich1@gmail.com 1, gustavo.rosales@unitec.edu2, alejandra_sanchez@unitec.edu 3

Abstract - The general purpose of this research was to develop a proposal for manufacturing vehicle license plates in Tegucigalpa, Francisco Morazán, using recycled PETG plastic filament in 3D printing through the use of industrial systems simulation. Part of the objectives was to identify critical stages of the process, for which the initial design of the plates was developed in SolidWorks and subsequently evaluated and adjusted using 3D printers like the Bambu Lab A1, identifying that the appropriate thickness should be at least 4 mm to ensure structural quality and proper layer adhesion and that the average printing time of part A would be 3 hours and 40 minutes, revealing that this factor would be the biggest obstacle to implementing this proposal. Through cost engineering, the economic benefits of manufacturing with recycled PETG were analyzed, demonstrating that this methodology reduces costs while promoting a sustainable and efficient additive manufacturing model. The analysis revealed that the proposed method yields a cost of L.90.53 per plate (this price is based on material cost), this cost being below the current cost of traditional plates which starting price is L.500 for two plates (this price includes all operational costs). The identification of critical stages in the process, supported by simulations, provided valuable insights for future large-scale implementations, offering an economically and environmentally responsible solution to the shortage of vehicle license plates in the country

Keywords: 3D Printing, Recycled PETG, Process Simulation, Additive Manufacturing, Cost Engineering

© Copyright 2025 Authors - This is an Open Access article published under the Creative Commons Attribution License terms Creative Commons Attribution License terms. Unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Date Received: 2025-04-23

Date Revised: 2025-09-09

Date Accepted: 2025-10-29

Date Published: 2025-12-19

1. Introduction

Honduras is experiencing a crisis in the transportation system due to the shortage of material used in the manufacture of vehicle plates nationwide. The Property Institute (IP), the regulatory body for the issuance of vehicle plates, is currently facing difficulties in meeting demand due to the problem of acquiring materials from its suppliers. Due to this crisis, vehicle plates have not been issued in traditional material, but rather provisional paper identifications have been used, which is unsafe and has generated commotion among citizens. [1]. Due to this problem, this research has arisen, which proposes the manufacture of vehicle plates in 3D printing and also the use of recycled PETG filament. Research carried out in Panama [2] and Honduras [3] have highlighted the feasibility of using materials such as recycled polymers for 3D printing. These investigations have applied various engineering methodologies from the Design of Experiments and the analysis through simulators [4]. The contributions of these promote good practices of sustainability and responsibility with the environment. In accordance with these initiatives, this project proposes to apply it in the manufacture of vehicle plates. 3D printing processes offer advantages such as rapid manufacturing of functional parts, shorter delivery times and lower costs in research and development [5]. As tools for carrying out this research, the SolidWorks computer-aided design software was used for the design used in the printing of vehicle plates, the FlexSim industrial process simulation software to simulate the printing process of the plates and the 3D printer instrument for printing the plates

These limitations, combined with the need to dissipate an ever-growing thermal power to ensure the correct functionality and preservation of mechanical and electronic components, have driven scientific research toward the development of innovative heat dissipation systems. Porous and periodic cellular materials (PCM) are highly promising multifunctional materials, with broad applications ranging from the aerospace and automotive sectors [4] to energy storage and heat transfer systems [5]. Among PCMs, truss-based PCMs carved out a prominent spot due to their superior structural resistance to both static and dynamic loads [6] and their heat dissipation capability, which can reach values up to seven times higher than that of an empty channel with a lower pressure drop compared to other non-truss-based options, leading to a thermal efficiency that outperforms typical heat sink media such as pin fins and cylinder banks [7]. Among truss-based lattices, the Kagome type exhibits isotropic mechanical responses under compression and shear and, unlike tetragonal PCMs, this behaviour remains unchanged after yielding [8]. Moreover, Kagome lattices provide a higher heat dissipation rate, up to 38%, for a fixed pumping power compared to the tetragonal counterpart, reaching values comparable to the X-type lattice [9]. For these reasons, several additional studies have been conducted to optimise Kagome performances further. Joo et al. [10] investigated the heat transfer capabilities of wire-woven bulk Kagome (WBK) made of aluminium helix wires in forced convection, analysing the effect of Kagome orientation as well by altering the flow pattern. The results showed that the "most closed" orientation possesses a considerably higher Nusselt number for each tested flow rate at the cost of a slightly increased pressure drop. However, the findings from Shen et al. [11] showed that the truss-cored Kagome achieves an overall Nusselt number up to 26% higher than a WBK, while maintaining a similar pressure drop. This is because a large portion of the ligaments is near the walls of the employed sandwich panels and so the flow blockage increases, leading to the formation of low-momentum vortices.

Although several studies have investigated heat transfer enhancement in lattice or porous structures, most available results in the literature concern sandwich panels, which can be regarded as ducts whose cross section is characterized by one side length largely exceeding the other one. In such configurations, the interaction between the channel’s perpendicular walls is negligible. Conversely, in the present study, the cross-sectional dimensions are comparable, resulting in mutual interactions between orthogonal walls that significantly influence the fluid pattern. Furthermore, previous works have mainly focused on fully developed flow, neglecting the effects of inlet length and conjugate heat transfer. The present work addresses these gaps by performing a systematic numerical and experimental analysis of compact lattice heat dissipation media, evaluating the combined effects of porosity, flow regime, and inlet length on both local and global thermohydraulic performance, expanding on the results found by this same research group in previous published studies on an X-type lattice [12–14].

The pressure drop, heat dissipation capability and thus thermal efficiency of a short smooth duct, namely K0, in which the working fluid is air, are investigated under two different flow conditions: fully developed flow and a flat inlet velocity profile, thereby accounting for inlet and outlet effects. Subsequently, the same analysis will be repeated on a duct equipped with the Kagome lattice, labelled K1, featuring a cell staggering equal to half the characteristic cell size in the transition from the first to the second row, which is then repeated periodically along the whole duct. The total porosity 𝜙 of the channel, defined as the ratio of the void to the entire internal volume, is set to be 87%. Obviously, for the K0 duct, the porosity is 100%. Results show that heat transfer is independent of the thermofluid entry length, thus demonstrating the advantage of using these heat dissipation media as highly compact solutions.

Afterwards, a topological analysis is conducted on the pillar size by decreasing and increasing their diameter, yielding porosities of 96% and 76% for the thinnest and thickest pillars, respectively. This analysis showed that, as porosity decreases from the highest to the lowest, the heat transfer rate doubles. This enhancement is to be attributed to the increased heat exchange area, rather than any modification of the flow pattern. This improvement, however, is accompanied by a rise in pressure losses and thus a saturation of the energy efficiency is found, indicating that there is a limit to how thick these pillars can be.

2. Numerical methodology

2.1. Governing equations

The governing equations of the problem under investigation are the three Navier-Stokes equations, namely the conservation of mass, momentum and energy. Assuming the fluid to be incompressible, they can be written as shown in Eqs. (1) – (3):

2.4.2 Sampling Method

The type of sampling used is non-probabilistic for convenience due to the availability of recycled PETG filament at present. With this type of selection sampling, relevant variations such as behavior and material consumption during printing were captured. This approach responded to the need to obtain material consumption data relevant to economic analysis. [6]

2.4.3 Sample

The research sample consisted of physical 3D printing using recycled PETG filament of 6 vehicle license plates. The 3D printing of six vehicle license plates allowed obtaining tangible data regarding material consumption, comparing and validating with the data obtained from the 3D printing software prediction.

In this sample, the benefits of simulation and physical 3D printing tests were combined, because the simulations provided predictions on the behavior of the prints, while the physical printing of six plates allowed validation of the simulation data helping to generate a detailed analysis of the material and the process.

2.4.4 Techniques and instruments applied Instruments

- 3D Printers (Bambu Lab A1): Used to conduct physical printing tests with recycled PETG filament, allowing the evaluation of the viability of vehicle plate production.

- FlexSim Software: A simulation tool that enables the modeling and optimization of the production process in a controlled environment, simulating different production and demand scenarios.

- SolidWorks Software: Used for the 3D design of vehicle plates, allowing the adjustment of dimensions and conducting structural simulations of the model before printing.

- Microsoft Excel: Employed for data analysis, recording results, and calculating costs associated with the production process, facilitating the management and comparison of key variables in the project.

Techniques

- Process simulation in software: Use of FlexSim to replicate the production flow in a virtual environment and evaluate the efficiency of the process.

- Process analysis: A technique to identify potential bottlenecks and optimize the production flow at each stage of the process.

2.4.5 Validation Methodology

The validation of this project was carried out in three main phases. The first phase consisted of conducting preliminary 3D printing tests with recycled PETG filament for the production of vehicle plates in a controlled environment, considering studies conducted with PETG demonstrate that it is a material with high chemical resistance, as well as the ability to withstand high temperatures and mechanical stresses. These pilot tests allowed for the analysis of the filament's effectiveness, recording data on material performance, print time, and filament consumption per plate. This initial process was essential for identifying potential errors and adjusting parameters, ensuring that the production methodologies were suitable for the study and thus reducing variations that could affect the final results.

The second phase of validation was carried out through a simulation of the printing process in FlexSim software. This simulation replicated the production flow in a virtual environment, allowing for a comparison of the data obtained from physical tests with the simulated results. This stage facilitated the analysis of the model's consistency and the identification of opportunities for improvement in the workflow, ensuring that the model accurately reflected the conditions observed in the real tests. The simulation was reviewed by experts to validate its accuracy regarding printing parameters and material consumption.

The third phase involved the review of these results by industrial engineering experts, who provided observations and feedback to validate that the proposed process met the standards of feasibility, efficiency, and sustainability, thus completing the comprehensive validation of the project

3. Analysis and Results

3.1 Design and Modeling of License Plates

3.1.1. Design Piloting and 3D Printing for Validation

The piloting process consisted of an iterative cycle that integrated the design in CAD software, 3D printing and the analysis of the piloting results, with the main purpose of validating the preliminary design of the vehicle plates. This process began with the development of the base model in SolidWorks, then this design was 3D printed to evaluate its characteristics and analyze points of improvement in the design so that it complied with the vehicle plate standards. For this reason, two tests were carried out, which resulted in two pieces resulting from the piloting tests. [6]

3.1.1.1. Initial Design

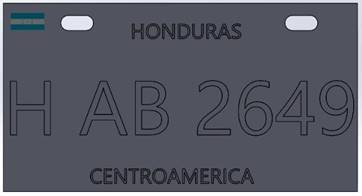

The development of the preliminary design of the license plate in the first pilot began with a basic SolidWorks model that served as a starting point for the pilot tests. This initial design considered the standard dimensions of vehicle license plates in Honduras, see Fig. 1. SolidWorks vehicle plate design 1:

Length: 30 cm

Width: 16 cm

Thickness: 2mm

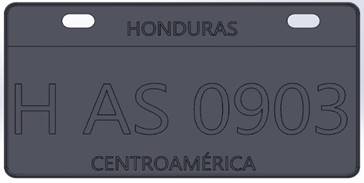

Following the evaluation of the first pilot, necessary adjustments were identified and a second, more detailed and complete design was developed. This model, see Fig. 2 SolidWorks vehicle plate design 2 included adjustments such as:

- Internal blue line: An internal line was added for the blue stripe characteristic of the Honduran plates. This line located 4 cm from the outer edge.

- Corner rounding: To improve functionality, corners were rounded to a radius of 1.03 cm. This reduces the risk of edge fractures and ensures a better aesthetic finish.

- Inner edge: An internal black border was generated using the offset tool, creating a uniform 8 mm border towards the inside of the plate, which gives it greater rigidity and an improved aesthetic appearance.

- Text Correction ("Central America"): In SolidWorks, the text "Central America" was adjusted to include the accent on the letter "e", ensuring that the design is correctly represented in print.

Design Piloting and 3D Printing for Validation

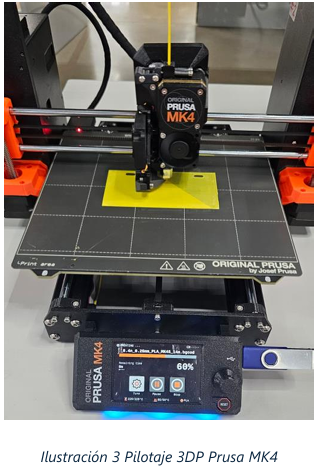

The first print run was carried out on a reduced-scale Prusa MK4 printer (40%) see figure 3, which allowed us to identify the necessary adjustments that had been made to SolidWorks design two. In the final stage, design two was printed on the Bambu Lab A1, adjusting the plate thickness to 4 mm for greater strength. Due to printer limitations, the plates were manufactured in two parts joined together afterwards.

Pilot validation was essential in additive manufacturing projects, such as vehicle license plates, as it allows preliminary designs to be evaluated and adjusted before their full implementation. This approach reduces costs associated with errors and minimizes material and time waste, taking advantage of rapid iterations in CAD and prototypes to solve problems at early stages [7].

3.1.2 Manufacturing Test Setup

At this stage, the printing parameters were defined and adjusted to ensure the quality and consistency of the 3D printed license plates with recycled PETG filament. The settings were established on the Bambu Lab A1 printer, ensuring a balance between quality, durability and efficiency in material consumption. The printing parameters were adjusted based on the results observed in the prototypes and were defined as follows:

- Extrusion nozzle temperature: 239 °C

- Printer base temperature: 64 °C

- Printing speed: 50 mm/

- Layer thickness: 2 mm

- Adjusted thickness: 4 mm

3.1.3 Physical Test Results

The results of the physical printing tests provided detailed information on the behavior of the recycled PETG filament and the quality of the printed vehicle license plates. As the plates were made in two pieces due to machine limitations, the data for each piece is specified:

The data obtained for part A include:

- Production Time: On average, each vehicle plate took 3 hours 54 minutes to

- Material Consumption: Each printed plate used an average of 45 grams of PETG filament.

The data obtained for part B include:

- Production Time: On average, each vehicle plate took 1 hour 24 minutes to

- Material Consumption: Each printed plate used an average of 61 grams of PETG filament.

The Fig. 5 Final result of printing vehicle license plates in 3D printing. shows the final product of the 3D printed license plate, this is the result of joining Part A and Part B. In order to reach this final product, a process was established that will be described in the following section.

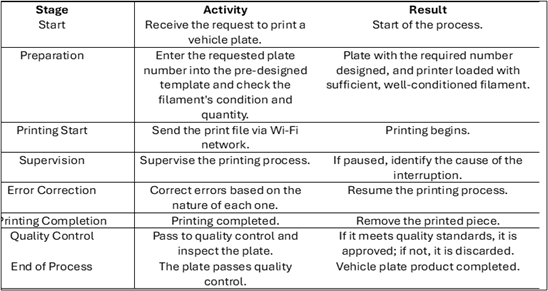

3.2 Print Process Flow Analysis

The process flow analysis helped to clearly visualize the operation of the process performed for 3D vehicle license plate printing. A summary table of the process flow diagram has been made, in which you can see the stages of the process, the activity performed at that stage, and the result obtained from that stage. See Table 1 Vehicle license plate 3D printing process

With the information on how the printing process is carried out, it was possible to identify the stages and critical stages that are important for the operation of the system.

3.2.1 Identification of Critical Steps

Through the analysis of the printing process, the critical stages were highlighted as follows:

- Filament check: If there is not enough filament load, the print will be incomplete. In case of a bad filament the print may fail.

- Continuous monitoring in printing: Be aware of any interruption in order to solve it and not generate major delays in the production line.

- Quality control: Do not approve a product that does not meet the requirements.

The critical stages above have been extracted from the flow chart that was used to clearly visualize the structure of each stage, how it is performed and what its result is, this helps to understand the flow of the printing process. The flow chart is in the full report of this research. This utility highlights [8] that process analysis through visual tools such as the flow chart, allows to visualize bottlenecks, inefficiencies and opportunities for improvement. Given the understanding of the 3D vehicle license plate manufacturing process, the activities are carried out in relation to the simulation model in FlexSim.

3.3.1. Piloting of the simulation model in FlexSim

As a preliminary stage of the research, a pilot test of the simulation model was carried out to validate it before carrying out larger-scale simulations. At this stage, the accuracy of the model in being able to replicate the process with the conditions observed in the physical 3D printing tests was identified, as well as the printing and machine preparation times through the simulations issued by the printing software.

3.3.1.1. Formulación del modelo de Simulación en FlexSim

The simulation of the process in FlexSim replicated the process of plate printing from receiving the order to make a license plate to the printed license plate. The processes were represented in the simulation by the tool objects that FlexSim provides. The replicated times are in units of seconds, so the current model that covers a time from 8 am to 5 pm is 32,400 seconds.

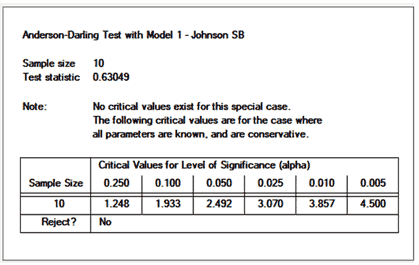

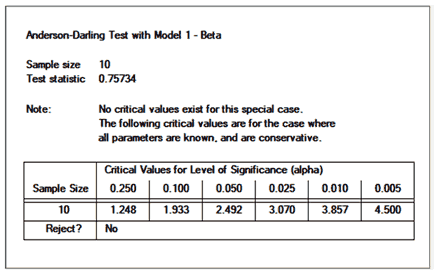

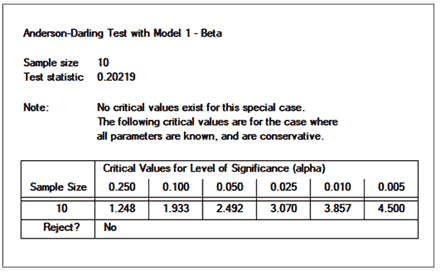

With the information collected from the observed times in the design, printing and joining processes, the processing times were configured with probabilistic distributions. The distributions for each of the printing and joining processes were made in the Expertfit software found within the same FlexSim software. The distributions are found in Table 2.

|

Activity |

Processing Price Distribution |

|

Piece A |

Johnson SB Distribution |

|

Piece B |

Beta Distribution |

|

Union |

Beta Distribution |

Table 2. Time Distribuition

Processing times with probabilistic distributions are observed in the following tables

3.3.1.2 Validation of the Simulation model in FlexSim

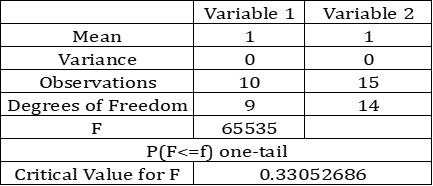

The simulation model performed in FlexSim to simulate the plate printing process must be statistically validated, the performance indicators that the simulation yields must be equal to the real data.

As shown in the table above, Table 6 Tests for two-sample variance, by means of the F test for variances of two samples it was possible to verify that the variances were equal, therefore, the T test was carried out assuming equal variances and the model was statistically validated. The validated model verifies that the time measurements and distributions carried out in Experfit were carried out correctly and can be used to propose a new model in Flexsim.

3.3.2 Simulation Results in FlexSim

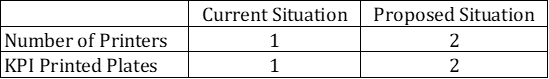

The current situation of the printing process has only one printer that is in charge of printing Part A and Part B and a station for joining parts, which in a day from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. is only capable of completing a full plate, which we can visualize as KPI Printed Plates in Table 7 .

To start with the proposed situation, the key part was to choose two printers, one printer being in charge of printing Part A and another to print Part B. By simulating the process we were able to Identify the bottleneck in the vehicle license plate manufacturing process, thereby analyzing the critical stage by which the process capacity is compromised. With the proposed situation of two independent printers for part A and part B in the simulation model, it is possible to manufacture two vehicle plates per work day. In the proposed simulation model there are three parameters that can be modified in quantity. The three parameters are: quantity of printers for Part A, quantity of printers for Part B and quantity of part joining stations. These parameters can be modified in Experimenter, which is a tool that FlexSim has, in which different scenarios can be evaluated by modifying the existing quantity of parameters, performing an analysis to be able to make informed decisions. Highlighting [9] that the simulation generates a great benefit for us by being able to modify parameters to visualize their improvement in the result of the process.

3.4 Economic feasibility

3.4.1 Cost analysis per plate

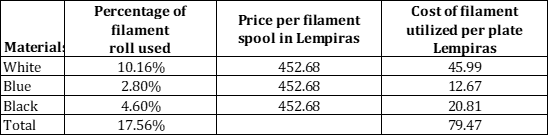

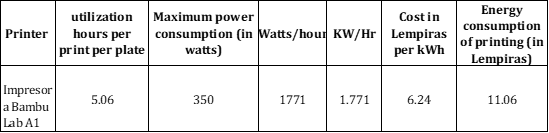

To determine the economic viability of the 3D license plate printing proposal, it began by analyzing the costs associated with printing license plates, such as filament consumption and energy expenditure. Detailed cost data can be found in the full report of this research.

The identification of filament consumption has been essential to be able to find the monetary cost per plate after printing. [10] The estimation of costs in the early stages of a project is essential to be able to evaluate budgets and analysis in an effective way. To estimate the total cost per plate, the energy consumption of the printers during the time they are working when manufacturing each plate was finally taken into consideration [11]. See Table 9.

Taking into account these factors that directly affect the production of vehicle license plates, it was estimated that the cost per plate would be L.90.53. The price is considered optimal and of great savings considering the costs of the metallic vehicle license plates that circulate in the country. Economic savings demonstrate a great benefit as well as the recycled material contributes to the reduction of environmental impact [11].

|

Cost of Roll Used per Plate (Lempiras) |

Printing Energy Consumption (Lempiras) |

Total Plate Cost (Lempiras) |

|

L79.47 |

L11.06 |

L90.53 |

Table 10. Cost of materials per plate

Bearing in mind the detailed costs in Table 8, which directly affect the production of vehicle plates, it was estimated that the cost per plate will be L.90.53. The price is considered optimal and a great savings considering the costs of metal vehicle plates that circulate in the country. The economic savings demonstrate a great benefit as well as the recycled material contributes to the reduction of environmental impact [12]

4. Discussion

A methodology was defined to manufacture vehicle plates using 3D printing with recycled PETG filament. It's important to explain that this material possesses the necessary resistance for the product in question. It withstands greater mechanical stresses, making it ideal for parts that need to be robust. Similarly, PETG has a higher melting point than PLA, which means it can tolerate higher temperatures without suffering deformation [13]

The design in SolidWorks and pilot tests on 3D printers such as Prusa MK4 and Bambu Lab A1 allowed for the adjustment of critical parameters such as the thickness, which had to be 4 mm to ensure strength and durability

FlexSim analysis and physical tests identified the bottleneck in printing Part A, with an average time of 3 hours and 40 minutes. These tests identified the need to evaluate scenarios to optimize efficiency through simulation and pointed out the need to improve the technology used in printing the plates

The simulation model in FlexSim validated that with one printer per part, only one complete plate is produced in an 8-hour workday. It was proposed to separate stations and assign one printer per part, increasing production to two plates per day. Using Experimenter, scenarios were evaluated to determine the optimal number of printers needed to increase production.

The average manufacturing cost per plate was estimated at 90.53 lempiras, considering the consumption of recycled PETG filament and electrical energy, using a Bambu Lab A1 multicolor printer. Currently the metallic license plates that traditionally has been used in Honduras have a price around L.500 per two plates. [14]. Though the cost previously mentioned is the final cost for citizens. Compared to the proposed, this makes 3D printing approach a financially attractive alternative. Further studies could refine this estimate and explore the impact of mass scale production

5. General conclusion

In general, the 3D printing process of vehicle plates with recycled PETG is economically viable, reducing manufacturing costs. However, the average printing time of 5 hours and 6 minutes limits the capacity to meet demand in Honduras. The computerized design of the plates meets the required measurements. Adding the possibility of exploring other production methods that require accelerating the process to make it more productive.

6. Recommendations

6.1 Research Recommendations

To expand the analysis of variables involved in 3DP, exploring different types of recycled filaments. In order to compare and study the efficiency, strength and durability of the materials.

Create a design that meets specifications but has a shorter print time for faster production and improved production capacity.

Use industrial printers that can print the plate at its standard scale, without the need to make the pieces separately and avoid joining them together, which delays production time.

For better quality research, future researchers are advised to simulate times on a printer that can print the plate in its size, thus speeding up the production process.

6.2 Recommendations for the Business Line or Group of Companies

The entities in charge of the production of vehicle license plates with the adoption of 3D printing technology can benefit the manufacturing process, due to its reduction in production costs and the environmental impact it generates by using recycled material [15] y [16].

Establishing alliances with suppliers of recycled materials would also strengthen the supply chain, promoting the circular economy in the industry and reaffirming the commitment to environmental sustainability.

The study of this research was conducted at the proposal level in the field of additive manufacturing (3D Printing), computer-aided design, and industrial systems simulation. The results of the research serve as support for decision-making based on the production of plates through 3D printing of vehicle plates using filament made from recycled PetG.

The tools used for the research and the 3D printing of vehicle plates can be replicated by other researchers who wish to assess the technical feasibility of additive manufacturing for plate production. Computer-aided drawing techniques and industrial systems simulation can be replicated to analyze the feasibility of other products that can be made through 3D printing.

References

[1] Mundo, E. (2023, 29 de junio). Escasez de placas de vehículos en Honduras genera preocupación en importadores. Diario El Mundo. View Article

[2] Marín, N., Serrano, M., Serrano, M., & Jaén, A. (2021). Propuesta de materiales reciclables para la fabricación de placas vehiculares en la República de Panamá. Revista De Iniciación Científica, 7(1), 54-59. View Article

[3] Sosa, G. (2024). Feasibility of manufacturing and utilizing recycled PET 3D printing filaments through design of experiments. Universidad Tecnológica Centroamericana (UNITEC).

[4] Aguilar, G., Santos, S., & Perdomo, M. E. (2024). Analysis of the Mechanical Properties of 3D Printed Structures and Comparison of Results through Simulations in Solidworks Software. Proceedings of the 10th World Congress on Mechanical, Chemical, and Material Engineering (MCM'24), Barcelona, Spain, Aug. 22-24, 2024. View Article

[5] Al Rashid, A., & Koç, M. (2023). Additive manufacturing for sustainability and circular economy: Needs, challenges, and opportunities for 3D printing of recycled polymeric waste. Materials Today Sustainability, 24, 100529. View Article

[6] Hernández Sampieri, R., Fernández Collado, C., & Baptista Lucio. (2018). Metodología de la Investigación. McGraw-Hill.

[7] Gibson, I., Rosen, D. W., & Stucker, B. (2015). Additive manufacturing technologies: 3D printing, rapid prototyping, and direct digital manufacturing. Springer. View Article

[8] Harrington, H. J. (1991). Business Process Improvement: The Breakthrough Strategy for Total Quality, Productivity, and Competitiveness. McGraw-Hill.

[9] Banks, J., Carson, J. S., Nelson, B. L., & Nicol, D. M. (2010). Discrete-event system simulation. Pearson.

[10] Barrios, C., & Miranda, M. (2006). Diseño de un sistema de uso didáctico para el análisis y cálculo de costos de producción (método tradicional) para la asignatura de ingeniería de costos de la facultad de ingeniería industrial de la Universidad Simón Bolívar. Universidad Simón Bolívar.

[11] Alonso, L. V. (2009). Ingeniería de Costos.

[12] Beltrán, J. (2023). Metodología y/o factibilidad del aprovechamiento de material (PLA, PETG) residual en la manufactura aditiva. Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira. View Article

[13] Herzog Cruz, J. L. (2022). Estudio del efecto de la temperatura en las propiedades mecánicas de probetas de PET-G fabricadas mediante modelado por deposición fundida. Trabajo Fin de Grado, Universidad de La Laguna, San Cristóbal de La Laguna, España. View Article

[14] Registro Vehicular. (n.d.). Preguntas frecuentes sobre registro vehicular. Instituto de la Propiedad de Honduras. View Article

[15] Gebler, M., Uiterkamp, A. J. M. S., & Visser, C. (2014). A global sustainability perspective on 3D printing technologies. Energy Policy, 74, 158-167. View Article

[16] Bolaños Zea, J. J. G. (2019). Reciclado de plástico PET. Universidad Católica San Pablo. View Article