Volume 12 - Year 2025 - Pages 381-387

DOI: 10.11159/jffhmt.2025.037

Design, Construction, and Modelling of an Automated Solar Water Heater System with AI-Based Optimization

Haifa El-Sadi and Sammy Riadi

1Wentworth Institute of Technology 550 Huntington, Boston, MA, USA 02115,

elsadih@wit.edu

Abstract - Solar water heating systems are a fantastic way to harness the sun's energy to heat water for domestic use. By converting solar energy into thermal energy, these systems can significantly reduce reliance on traditional energy sources and lower energy costs. The aim of this project is to improve the design of solar water heater components such as solar collectors, water tank, piping system, and pump using SolidWorks. The SolidWorks CFD Simulation utilized predefined initial conditions, including solar radiation settings, to simulate conditions akin to Boston, Massachusetts, in early July, around noon, which is considered optimal for real-life testing. Through this simulation, a maximum surface temperature of 234 degrees Fahrenheit was attained. Factors such as head loss in each connection and variations in water temperature within the piping and the pump have not been fully accounted for. The flow rate of water at the intake and outtake points may fluctuate based on the water's temperature, introducing uncertainties into the system's performance. Changes in pipe sizing could alter the flow dynamics, affecting the overall efficiency of the system. These complexities highlight the need for further analysis and refinement to ensure accurate modelling and interpretation of results. AI is used to enhance the efficiency of solar tracking systems by real-time sun tracking using AI algorithms which can analyse real-time data from sensors to accurately predict the sun's position and adjust the solar panels accordingly. The temperatures were taken every 15 minutes for 45 min total as the solar collector absorbs more energy, the temperature of the stored fluid (and the collector itself) increases rapidly to 176 F.

Keywords: CFD, pump, Design, Solar panel, sensors

© Copyright 2025 Authors - This is an Open Access article published under the Creative Commons Attribution License terms Creative Commons Attribution License terms. Unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Date Received: 2024-12-17

Date Revised: 2025-09-06

Date Accepted: 2025-09-28

Date Published: 2025-11-26

1. Introduction

Solar water heaters are designed to be powered by the sun, a process dating back to ancient Roman times. American Indians used solar energy to heat their homes. During the 1500s, the Dutch began to use glass walls to increase the exposure of the sun to grow their vegetables year-round. In the 1880s, solar water heaters began to circulate in Baltimore and made their way to California and Florida. Solar water heaters then began to fade slightly due to cheap natural gas and electric power. Solar energy then took another turn and began to rise in 1973 due to the oil embargo and rising oil/natural gas prices. Today, solar power is becoming more prevalent as time goes on to combat climate change and pollution and offers lower costs than oil or gas. The solar water heater is just one application of clean energy and one we would like to focus on. Extensive work on improving the thermal efficiency of solar water heaters resulted in techniques to improve the convective heat transfer. Passive technique has been used to augment convective heat transfer. These techniques, when adopted in solar water heaters proved that the overall thermal performance improved significantly [1]. Heat exchangers are indeed a critical component of solar water heating systems. They play a crucial role in transferring heat from the solar collector to the storage tank.

El-Sadi et al.'s work on designing and analysing different heat exchangers is valuable for optimizing the performance of solar water heating systems [2, 3]. On the other hand, El-Sadi et al.'s research on different heat exchanger sizes such as micro and macro scales is valuable for optimizing the performance of solar water heating systems. Where the thermal efficiency of the heat exchanger can be influenced by factors like the surface area, flow rate, and temperature difference [4]. E. Natarajan et. al. research showed that the fluids with nanosized solid particles suspended in them are called “nanofluids.” The suspended metallic or non-metallic nanoparticles change the transport properties and heat transfer characteristics of the base fluid. Nanofluids are expected to exhibit superior heat transfer properties compared with conventional heat transfer fluids [5]. Also, previous studies revealed that a theoretical and experimental analysis of the thermal performance of a solar water heater prototype with an internal exchanger using a thermosiphon system [6]. Jamar et al. discussed the latest developments and advancements in solar water heaters, focusing on three key components that can significantly impact the system's thermal performance. Also, it provides a comprehensive overview of solar water heater technology, including a detailed discussion of various solar collector types., including both the non-concentrating collectors (flat plate collector, evacuated tube collector) and the concentrating collectors (parabolic dish reflector, parabolic trough collector) [7]. While Mostafaeipour et. al. pioneered a new conceptual model for solar water heater application in hot and dry regions, the extensive applicability of these systems, considering factors like geographical location, infrastructure, interactions, financial support, economic issues, and cultural-social-political issues, has not yet been thoroughly investigated [9].

Traditional solar water heater relies on sensors to follow a predictable path based on GPS coordinates or simple logic. Consequently, while they move along a set track to remain perpendicular to the sun's rays, they often fail to account for real-time environmental changes like cloud cover or shade. The objective of this project is to enhance the performance of solar tracking systems by implementing AI algorithms. These algorithms will analyse real-time sensor data to accurately predict the sun's position and adjust the solar heater water accordingly.

2. Design and CFD Analysis

2.1 Design

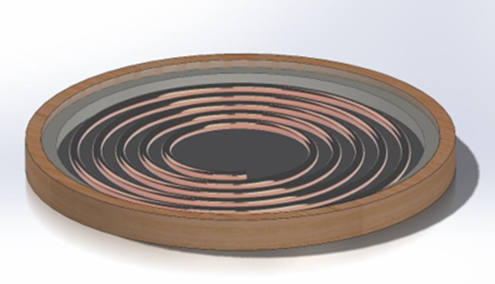

SolidWorks, a computer-aided design (CAD) software, was used to create five designs. The chosen design shown in Figure 1 was remodelled to fit new criteria and goals. These changes can be observed in Figure 2. The propeller guards were removed from the design plan.

SolidWorks has been used to design and analyze the solar water heater system. Different design iterations have been created and modified, allowing for rapid experimentation and optimization. As shown in Figure 1, the 3D models of design of Solar Collector Piping provide a clear visual representation of the system, aiding in understanding the system.

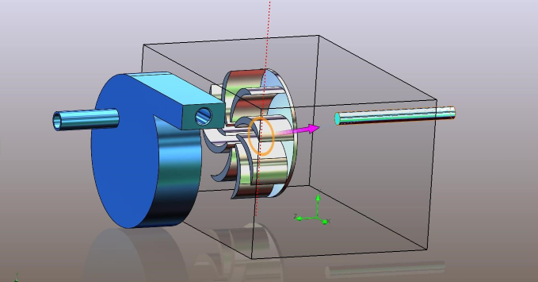

Engineering equation solver (EES) [8] has been used to simulate heat transfer within the system, helping to predict thermal performance under different conditions Using SolidWorks to design and analyse multiple pump models including the impeller design, as shown in figure 2, can help to identify the most efficient design, the most efficient pump design was 82.8%. Figure 3 shows the design for Dual Axis Collector Stand including the collector, pump and the stand.

2.2 CFD analysis

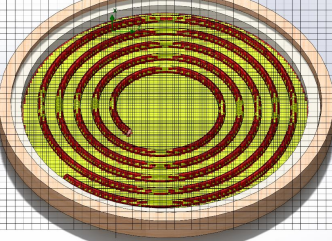

CFD analysis is used to optimize solar collector design and to simulate the flow of heat transfer fluid through the collector. Also, CFD is used to estimate the temperature distribution within the collector. CFD package is used to solve Navier-Stokes equations for three dimensional and steady state Newtonian fluid flow. It enables the use of different discretization schemes and solution algorithms, together with inlet velocity of 1.46 ft/s as a boundary conditions. The solar collector meshing shown in Figure 4 was executed using a solid mesh with the highest standard refinement level, using an element size of 0.03 inches, this process generated a total of 375,647 computational elements. The accuracy of the number of calculations is paramount, and having a high-quality mesh is crucial to achieving low percentage errors when comparing the simulated and calculated values.

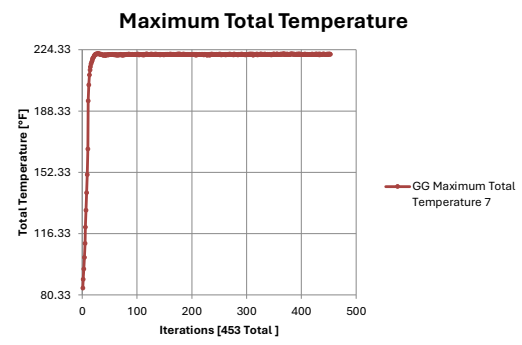

Figure 5 presents the convergence plot for the solar collector, illustrating how the simulation computed the temperatures.

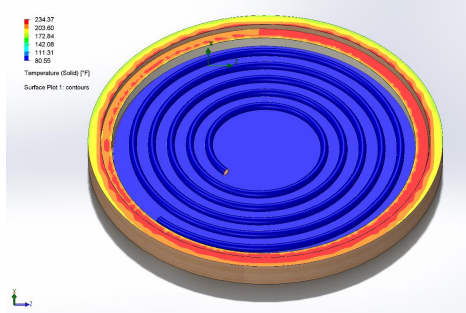

Figure 6 shows the temperature contour, which illustrates the temperature increase of the water as it passes through the solar collector, reaching a maximum of 234°F.

For three-dimensional, incompressible and steady state Newtonian fluid, the continuity equation, the equation of motion and energy equation are:

Where V is the tangential velocity, Re is Reynolds number, . DT/Dt is the rate of temperature change, and α is the thermal diffusivity. The CFD package is used to solve Navier-Stokes equations. It enables the use of different discretization schemes and solution algorithms, together.

3. Manufacturing Process

- Shaping the Pipe: a. Use the pipe bender to carefully bend copper into a spiral shape b. Start with an initial diameter of 24 inches and gradually increase the angle until it is about 6 inches in diameter in the center.

- Assembling the Collector: a. Start with screwing on the pieces of the 3D printed rim onto the wooden base b. Cut insulation into the correct shape and to the bottom and sides of the inside of the collector. c. Place aluminum backing on the bottom side of the inside of the collector and screw it into the wooden base on top of the insulation as shown in figure 7. d. Take copper piping and use pipe fasteners to secure it to the base. e. Bring the collector to the painting area and spray the paint on the internals of the collector black. f. Install tempered glass on the very top of the collector.

- Assembling Pump a. Submit STL files for 3D printing. b. Assemble pump along with DC Motor. Connect pipes to the pump and water bucket. As shown in figure 8.

3.1 Assembling and Testing

The system was set up by first connecting the solar collector to the pump. Before starting the experiment, the ambient environmental conditions were recorded, including the air temperature, atmospheric pressure, and cloud cover. The solar collector was then placed in direct sunlight for 15 minutes to allow for initial heating.

Following this, the temperature of the water in the bucket was recorded. The pump was then activated, and the temperature of the water exiting the collector was recorded. A complete diagram of the system is provided in Figure 9.

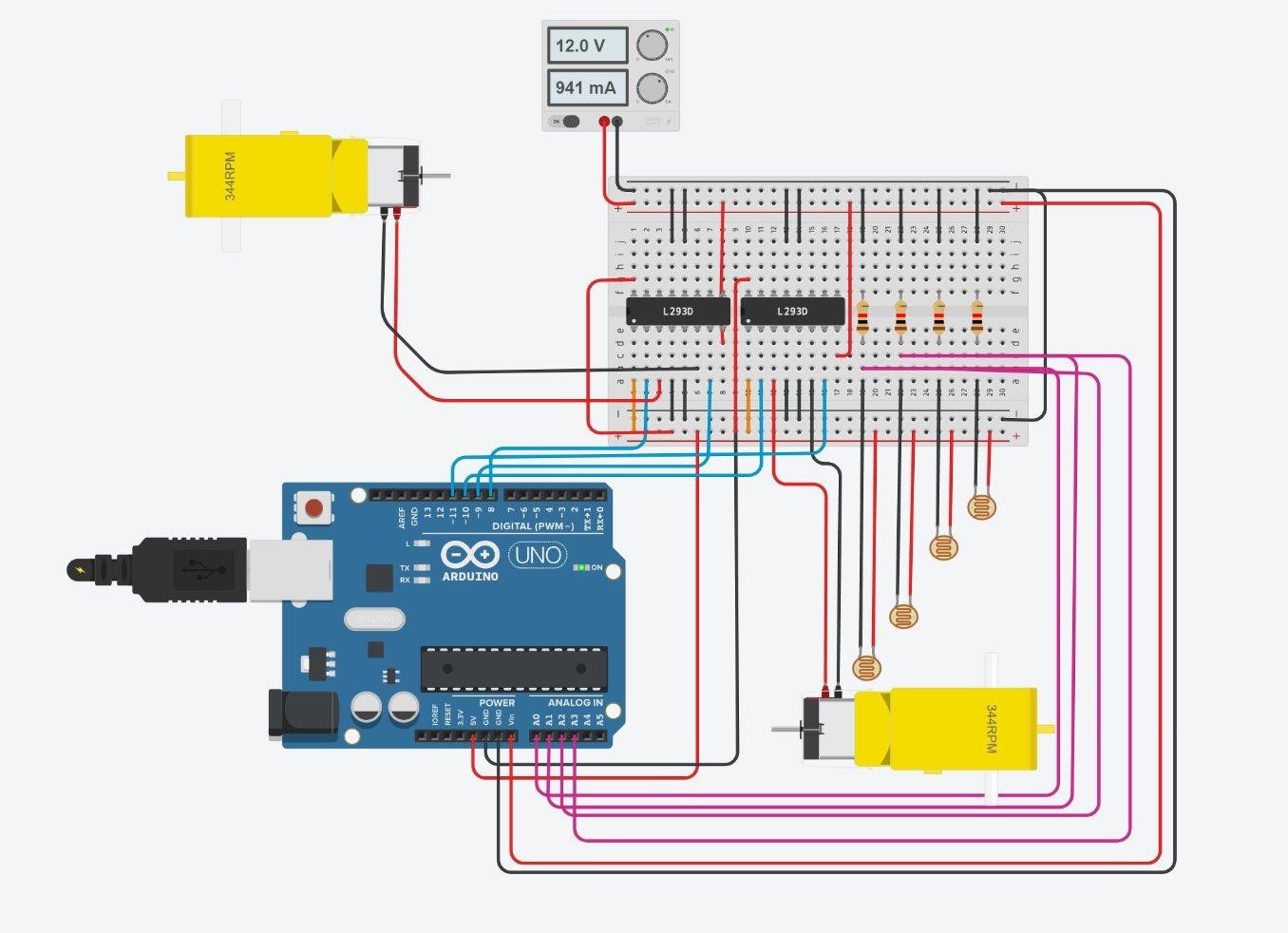

Artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms are employed to analyse data from sun sensors, enabling the precise, real-time determination of the sun's position. Figure 10 shows the circuit model in Tinker CAD, The most powerful feature of tinker CAD is the ability to run a live simulation of your circuit.

4. Results

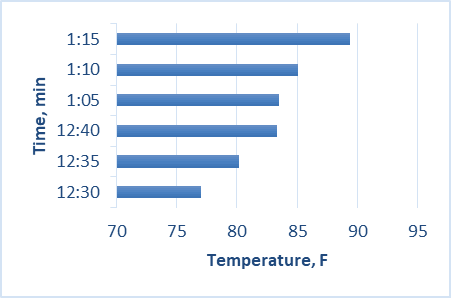

To simulate realistic operating conditions, the solar radiation settings were configured to replicate the environment of Boston, Massachusetts, during early July, at approximately noon. This period represents the optimal conditions for the system's real-life performance. Throughout the experimental testing, the temperature of the continuous water flow was recorded every five minutes. The solar water heater system successfully heated the water flow to a maximum temperature of 89.4°F, as illustrated in Figure 10.

Test 1: Continuous Flow

The first test involved a continuous flow of water, where the system's ability to convert solar energy into usable heat was successfully demonstrated. Solar radiation settings were configured to simulate the optimal conditions of an early July noon in Boston, Massachusetts. During this test, the temperature of the continuous water flow was recorded every five minutes. The system successfully heated the water to a maximum temperature of 89.4°F, as depicted in Figure 11.

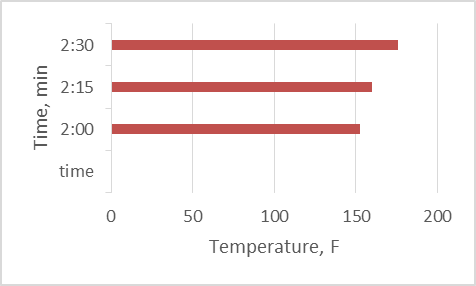

Test 2: Non-Continuous Flow

A second test, which involved allowing the water to remain in the collector for 15 minutes at a time (a non-continuous flow system), yielded significantly higher temperatures and better results. This test was a significant success and clearly showed the collector's effectiveness at heating water, as the water exited at a much higher temperature. As shown in Figure 12, the temperature of the stored fluid in the collector was measured every 15 minutes. The initial 15-minute period saw a rapid temperature increase to 152.4°F, followed by a further rise to 160°F in the second 15-minute interval, and finally reaching a maximum of 176°F. This rapid heating is especially noticeable in non-continuous flow systems where heat is not constantly being removed.

The 45-minute test served as a preliminary, proof-of-concept study to ascertain the viability of the proposed methodology. This test is part of a phased project, with longer duration testing scheduled for a later stage, contingent upon budget availability and the absence of constraints hindering more extensive data collection. Additionally, the limited accessibility of the test location precluded long-term monitoring during this initial phase.

Solar Tracking System

An additional successful component of this project was the development of a solar tracking system. This system was designed to optimize energy capture by continuously adjusting the solar panels' position to follow the sun's path. While assembling the motors to the base and collector frame, we encountered some initial challenges, including alignment issues and motor synchronization problems. These setbacks were overcome through careful calibration and iterative adjustments, ensuring the motors operated smoothly and accurately.

5. Conclusion

This research involves the design and analysis of an active solar energy system that integrates a comprehensive set of components: a water tank, a pump, a piping system, and a solar collector.

In contrast to passive systems that rely on material and architectural design for heating and lighting, this active system uses a water pump to circulate fluid through the solar collector. The core component, the solar collector, is designed to capture and absorb solar radiation, converting it into thermal energy that is then transferred to the circulating water. The heated water is subsequently stored in an insulated tank for use.

The system was specifically designed to optimize energy capture by continuously adjusting the position of the solar panels to track the sun's path. This real-time sun tracking is managed by an AI algorithm that processes data from sun sensors to accurately predict the sun's position and adjust the panels accordingly.

Data collection was conducted over a 45-minute period, with temperatures recorded every 15 minutes.

The non-continuous flow system facilitated a rapid temperature increase in the stored fluid, reaching a maximum of 176°F. It should be noted that the flow rate at the intake and outtake points fluctuated with the water's temperature, which introduced some uncertainty into the system's performance. Additionally, changes in pipe sizing could alter flow dynamics and overall efficiency. These complexities highlight the need for further analysis and refinement to ensure accurate modeling and interpretation of results.

Solar water heaters are versatile and can be utilized in various applications. Their most common use is providing domestic hot water for homes and businesses. They can also be employed for heating and cooling buildings. Furthermore, unglazed collectors offer a cost-effective solution for heating swimming pools, while high-temperature collectors are specifically designed to generate steam for electricity production in large power plants.

References

[1] S. Jaisankar, J. Ananth, S. Thulasi, S.T. Jayasuthakar, K.N. Sheeba, "A comprehensive review on solar water heaters", Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews , Volume 15, Issue 6, August (2011), Pages 3045-3050, ELSEVIER. View Article

[2] Haifa El-Sadi, Herb Connors, "Experimental studies of Heat Exchangers for Diesel Generator", International Journal of Advanced Network, Monitoring and Controls. Volume 8, No.3, (2023). View Article

[3] Haifa El-Sadi*, Joe Aitken, Jason Ganley, David Ruyffelaert, Cam Sweeney", Design Heat Exchanger: optimization and efficient", International Journal of Advanced Network, Monitoring and Controls, Volume 05 (2020), Issue 3, Page range: 30-35. View Article

[4] Haifa El-Sadi, Nabil Esmail and Andreas K. Athienitis, "High Viscous Liquids as a Source in Micro- Screw Heat Exchanger: Fabrication, Simulation and Experiments", 10.1007/s00542-006-0366-x, 0946-7076, Journal of Microsystem Technologies, (2007) View Article

[5] E. Natarajan and R. Sathish, "Role of nanofluids in solar water heater", The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, special issue - original article, Published: 01 July (2009) View Article

[6] P.M.E. Koffi, H.Y. Andoh, P. Gbaha, S. Touré, G. Ado, "Theoretical and experimental study of solar water heater with internal exchanger using thermosiphon system", Energy Conversion and Management, Volume 49, Issue 8, August (2008), Pages 2279-2290 View Article

[7]A. Jamar, Z.A.A. Majid, W.H. Azmi, M. Norhafana, A.A. Razak, "A review of water heating system for solar energy applications", International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, Volume 76, August 2016, Pages 178-187 View Article

[8] Haifa El-Sadi, "Using Engineering Equation Solver (EES) to Solve Engineering Problems in Mechanical Engineering", Paper No. IMECE2018-86078, pp. V005T07A040; 4 pages, doi:10.1115/IMECE2018-86078, 2018 View Article

[9] Ali Mostafaeipour, et. al., "A conceptual new model for use of solar water heaters in hot and dry regions", Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments, Volume 49, 2022 View Article