Volume 12 - Year 2025 - Pages 364-373

DOI: 10.11159/jffhmt.2025.035

Heat Transfer Enhancement through Thermal Dispersion in Hybrid Nanofluid Saturated Mixed Convection along a Horizontal Cone

Nayema Islam Nima 1, Shahina Akter1, Jahangir Alam3

1Department of Physical Sciences, Independent University, Bangladesh (IUB), Dhaka 1229, Bangladesh; nayema@iub.edu.bd.

2Department of Quantitative Sciences, International University of Business

Agriculture and Technology, Dhaka 1230, Bangladesh; shahina.qs@iubat.edu.

3Department of Computer Science and Mathematics, Bangladesh Agricultural

University, Mymensingh-2202, Bangladesh. jahangiralam.csm@bau.edu.bd.

Abstract - This study explores the influence of thermal dispersion on mixed convection flow of a hybrid nanofluid past a horizontal cone. The working fluid is ethylene glycol containing cylindrical alumina (Al₂O₃) and silica (SiO₂) nanoparticles in equal volume fractions. Compared with a single alumina-based nanofluid, the hybrid suspension exhibits significantly improved thermal transport capability. To analyze the problem, the governing nonlinear partial differential equations are reduced to ordinary differential equations using similarity transformations, and the resulting system is solved numerically with the Bvp4c method. The investigation shows that suction strongly enhances the heat transfer rate by reducing the thickness of the thermal boundary layer, while injection diminishes it, particularly under forced convection conditions. Thermal dispersion is found to decrease heat transfer efficiency by weakening the near-wall temperature gradient, with its impact being more pronounced in forced and mixed convection regions. In contrast, a higher Biot number consistently increases heat transfer, with stronger effects observed as the flow approaches free convection dominance. Overall, the results demonstrate that hybrid nanofluids, when coupled with optimized boundary conditions, can deliver substantial improvements in convective heat transfer performance. These findings underscore the potential application of such fluids in advanced cooling systems, heat exchangers, and energy-related technologies where efficient thermal regulation is critical.

Keywords: dispersion, suction/injection, hybrid nanofluid, ethylene glycol, forced convection.

© Copyright 2025 Authors - This is an Open Access article published under the Creative Commons Attribution License terms Creative Commons Attribution License terms. Unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Date Received: 2025-06-01

Date Revised: 2025-09-17

Date Accepted: 2025-10-01

Date Published: 2025-11-26

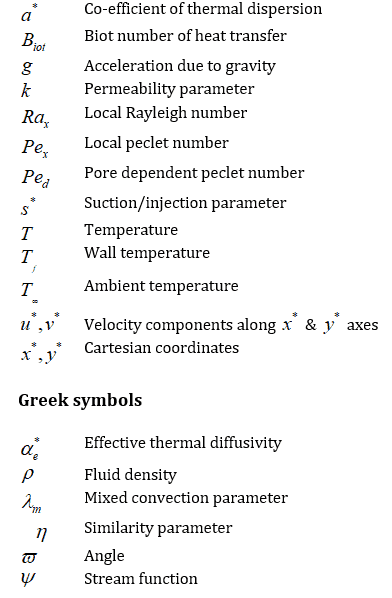

Nomenclature

1. Introduction

Mixed convection arises when buoyancy and forced flow act together. It is a critical mechanism in compact thermal systems such as electronics cooling, solar collectors, and heat exchangers. By influencing boundary-layer behavior across Reynolds–Grashof ranges, mixed convection directly shapes thermal performance. Previous studies have shown that geometry and orientation strongly affect flow structures and heat transfer. This makes mixed convection especially important in porous and non-planar domains (Amran et al. [1]). Recent experimental and numerical research confirms that nanofluids and hybrid nanofluids can enhance heat transfer in forced and mixed convection regimes. Compared with base fluids, they increase Nusselt numbers and thin thermal boundary layers (Roy & Akter [2]; Ali et al. [3]; Atofarati et al. [5]). These results reinforce the link between convection regimes and nanoparticle-enhanced transport.

Nanofluids, which are suspensions of nanoparticles in conventional base fluids, have attracted wide attention in thermal sciences. They improve thermal conductivity, adjust viscosity, and strengthen convective heat transfer (Choi [5]). Building on this concept, hybrid nanofluids combine two or more different nanoparticles. Such mixtures provide synergistic improvements in thermal transport compared to mono nanofluids (Sarkar et al. [6]; Sundar et al. [7]). Many studies have confirmed their enhanced stability and heat transfer behavior across various applications. For example, Shaik et al. [8] demonstrated the superior thermophysical properties of Cu–Graphene/water hybrid nanofluids. Sarfraz et al. [9] compared thermal conductivity models and showed consistent improvements with hybrid suspensions. Shahid et al. [10] highlighted the role of mixed convection in cavity flows with hybrid nanofluids. Asghar et al. [11] extended this analysis by incorporating magnetic field and heat generation effects (Ibrahim et al. [12]; Theeb et al. [13]).

Despite these advances, the influence of thermal dispersion has not been widely examined. Thermal dispersion results from microscopic conduction and particle-induced mixing, and it can strongly alter heat transport in porous systems. For instance, Wahid et al. [14] studied radiative mixed convection of hybrid nanofluids near a vertical flat plate and reported the sensitivity of heat transfer to Soret and Dufour effects mechanisms related to dispersion. Riaz et al. [15] investigated hybrid nanofluids in cylindrical systems and emphasized geometry-driven variations in flow and temperature. Rashid et al. [16] analyzed suction and magnetic effects over stretching surfaces, highlighting the importance of boundary conditions. More recently, Wahid et al. [17] and Mahdy et al. [18] modeled mixed convection in porous media and demonstrated that permeability and dispersion strongly influence forced–natural convection interactions. However, none of these works directly studied thermal dispersion in hybrid nanofluid flow over a horizontal cone.

Hybrid nanofluids have been widely examined in mixed convection flows (Roy & Akter [2]; Shahid et al. [10]; Asghar et al. [11]). Yet most studies focused on nanoparticle composition, radiation, magnetic fields, or suction effects, usually in flat or stretching surface configurations. The explicit role of thermal dispersion has been largely overlooked. Wahid et al. [14] and Riaz et al. [15] examined related transport mechanisms, but did not address hybrid suspensions in detail. Mahdy et al. [18] and Wahid et al. [17] explored porous domains, but concentrated on permeability and magnetic influences rather than dispersion itself.

This gap is significant because dispersion modifies temperature gradients and reshapes heat transport characteristics. To address it, the present work investigates the combined effects of thermal dispersion, suction/injection, and Biot number on hybrid nanofluid flow over a horizontal cone. The working fluid is an Al₂O₃–SiO₂/ethylene glycol hybrid suspension. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive study that incorporates thermal dispersion into the analysis of hybrid nanofluid mixed convection over a horizontal cone. The findings provide new insights for designing efficient thermal management and energy systems.

2. Mathematical modelling

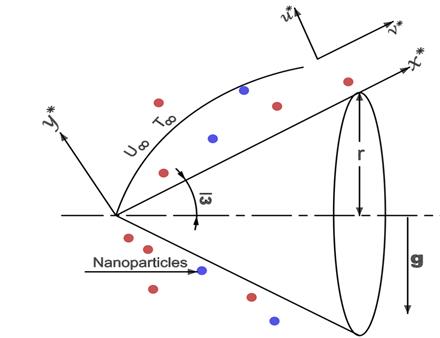

This study considers a steady, laminar, mixed convection boundary layer flow over a semi-vertically

inclined horizontal cone embedded within a porous medium saturated by fluid,

where the ambient temperature is denoted by ![]() .The cone surface is subjected to convective

heating from a warm hybrid nanofluid maintained at a uniform temperature

.The cone surface is subjected to convective

heating from a warm hybrid nanofluid maintained at a uniform temperature ![]() , with a spatially varying

heat transfer coefficient

, with a spatially varying

heat transfer coefficient ![]() along the surface. The coordinate system for the

flow configuration is illustrated in Figure 1. The

along the surface. The coordinate system for the

flow configuration is illustrated in Figure 1. The ![]() axis

is taken along the surface of the semi-vertically inclined horizontal cone,

measured from the cone vertex, while the

axis

is taken along the surface of the semi-vertically inclined horizontal cone,

measured from the cone vertex, while the ![]() axis

is oriented normal to the surface into the fluid. Employing the Boussinesq

approximation, the governing conservation equations namely, the continuity,

momentum and energy equations as Ferdows et al. [19], Sarfraz et al. [20] are

formulated, incorporating thermal dispersion effects and a convective boundary

condition at the surface.

axis

is oriented normal to the surface into the fluid. Employing the Boussinesq

approximation, the governing conservation equations namely, the continuity,

momentum and energy equations as Ferdows et al. [19], Sarfraz et al. [20] are

formulated, incorporating thermal dispersion effects and a convective boundary

condition at the surface.

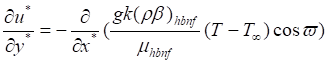

![]() (1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

![]() (3)

(3)

Boundary conditions

![]() at

at![]()

![]() at

at![]() (4)

(4)

Where  (5)

(5)

Here ![]() are effective thermal, constant thermal and

coefficient of thermal dispersion respectively.

are effective thermal, constant thermal and

coefficient of thermal dispersion respectively. ![]() value

is between

value

is between![]() to

to ![]() .

.

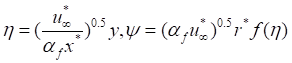

Transformations

,

,![]() (6)

(6)

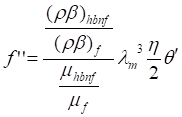

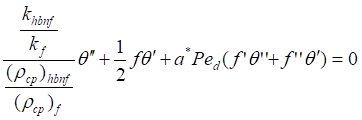

Using (5) and (6), transformed equations (1-4) are as follows:

(7)

(7)

(8)

(8)

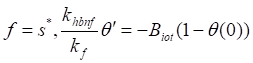

Boundary Conditions

at

at ![]()

![]() at

at ![]() (9)

(9)

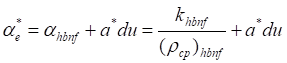

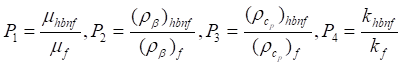

Mononanofluid and Hybrid nanofluid properties are

shown in Table 1. and Table 2. Different physical parameter can be defined are

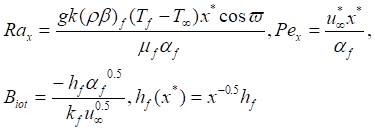

as follows: ![]() =

=![]()

According

to Sarfraz et al. [12], the shape factor for the nanoparticles ![]() is

selected in the aforementioned expressions, as our study focuses on

cylindrical-shaped nanoparticles.

is

selected in the aforementioned expressions, as our study focuses on

cylindrical-shaped nanoparticles.

Table 2. Physical properties of nanoparticles and basefluid

|

Physical Properties |

Nanoparticles |

Base Fluid |

|

|

|

Alumina |

Silica |

Ethylene glycole |

|

|

765 |

745 |

2430 |

|

|

46 |

1.38 |

0.253 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3970 |

2220 |

1115 |

(10)

(10)

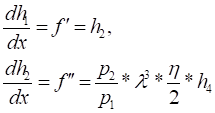

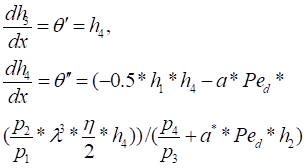

3. Numerical solution

The nonlinear ordinary differential equations, derived from the governing partial differential equations via similarity transformations, are solved numerically using MATLAB’s bvp4c solver. This approach, well-suited for two-point boundary value problems, reformulates the higher-order system into first-order equations, defined alongside boundary conditions through function handles. An initial guess, guided by physical considerations, is supplied to initiate the computation. The bvp4c algorithm employs a collocation method with adaptive mesh refinement, ensuring convergence by iteratively minimizing residual errors until the prescribed tolerance is satisfied.

Now substituting ![]() for

for ![]() and also considering

and also considering

![]()

The first order equations are

Boundary conditions

![]() ,

, ![]()

![]() ,

, ![]()

The variable![]() represents the boundary

condition on the left side, while

represents the boundary

condition on the left side, while ![]() denotes the boundary condition on the right. To

assess the accuracy of the present numerical solutions, a comparison was

carried out with the results reported by Ferdows et al. [19] for a particular

case, as summarized in Table 3 and Table 4. The close agreement between both

sets of results verifies the robustness and accuracy of the proposed

computational method.

denotes the boundary condition on the right. To

assess the accuracy of the present numerical solutions, a comparison was

carried out with the results reported by Ferdows et al. [19] for a particular

case, as summarized in Table 3 and Table 4. The close agreement between both

sets of results verifies the robustness and accuracy of the proposed

computational method.

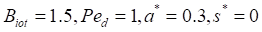

Table 3. Biot

number ![]() and Dispersion effect on

and Dispersion effect on ![]() for the regular fluid (

for the regular fluid (![]() )

)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Present study |

Ferdows et al. [19] |

|

10000000 |

0 |

1.0000 |

1.0000 |

|

1.5 |

0 |

1.0000 |

1.0000 |

|

1.5 |

10 |

1.0000 |

1.0000 |

Table 4. Biot number ![]() and

Dispersion effect on

and

Dispersion effect on ![]() for the regular fluid (

for the regular fluid (![]() )

)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Present study |

Ferdows et al. [19] |

|

10000000 |

0 |

0.5644 |

0.5644 |

|

1.5 |

0 |

0.4101 |

0.4100 |

|

1.5 |

10 |

0.2539 |

0.2538 |

4. Results discussion

In this analysis, the

nanofluid contains 4% volume fraction of alumina nanoparticles (![]() ), whereas the hybrid nanofluid consists of

2% alumina and 2% silica nanoparticles (

), whereas the hybrid nanofluid consists of

2% alumina and 2% silica nanoparticles (![]() ).

The values of

).

The values of ![]() are tabulated in Table 5 to

illustrate the effect of the mixed convection parameter on the velocity profile

at the surface. Here,

are tabulated in Table 5 to

illustrate the effect of the mixed convection parameter on the velocity profile

at the surface. Here, ![]() corresponds to pure

forced convection, and increasing

corresponds to pure

forced convection, and increasing ![]() shifts the flow

from forced to mixed and eventually toward free convection. The table presents

the impact of

shifts the flow

from forced to mixed and eventually toward free convection. The table presents

the impact of ![]() for the mono nanofluid, hybrid

nanofluid, and the regular base fluid for comparison.

for the mono nanofluid, hybrid

nanofluid, and the regular base fluid for comparison.

Table

5. Mixed convection effect on  for the the

values

for the the

values

The table illustrates how

the dimensionless wall shear, ![]() varies with

varies with ![]() , the mixed convection parameter. Regular

fluid, mono nanofluid, and hybrid nanofluid exhibit the similar behaviour at

surface as buoyancy effects are negligible. As

, the mixed convection parameter. Regular

fluid, mono nanofluid, and hybrid nanofluid exhibit the similar behaviour at

surface as buoyancy effects are negligible. As ![]() increases,

indicating a shift toward mixed and free convection,

increases,

indicating a shift toward mixed and free convection, ![]() rises for all fluids due to enhanced wall

shear from buoyancy-driven momentum transport. The mono nanofluid shows

slightly higher

rises for all fluids due to enhanced wall

shear from buoyancy-driven momentum transport. The mono nanofluid shows

slightly higher ![]() at lower

at lower ![]() . At higher

. At higher ![]() , the

hybrid nanofluid surpasses it. This

reflects the synergistic effect of the two nanoparticle types in enhancing

convective momentum transfer. The regular fluid consistently exhibits the

lowest

, the

hybrid nanofluid surpasses it. This

reflects the synergistic effect of the two nanoparticle types in enhancing

convective momentum transfer. The regular fluid consistently exhibits the

lowest ![]() , highlighting the significant

role of nanoparticles in increasing skin friction. Overall, the table

demonstrates that mixed convection strengthens wall shear and that hybrid

nanofluids provide superior momentum transport compared to mono nanofluids under

identical flow conditions.

, highlighting the significant

role of nanoparticles in increasing skin friction. Overall, the table

demonstrates that mixed convection strengthens wall shear and that hybrid

nanofluids provide superior momentum transport compared to mono nanofluids under

identical flow conditions.

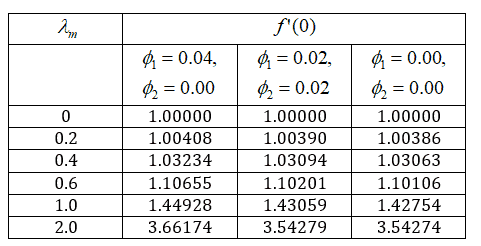

demonstrates the influence of suction and injection on the velocity profile of the boundary layer flow. Suction, which extracts fluid from the surface, reduces the boundary layer thickness and sharpens the velocity gradient near the wall, thereby stabilizing the flow. In contrast, injection introduces additional fluid into the boundary layer, which increases its thickness and leads to a relatively flatter velocity distribution. When comparing different fluids, the hybrid nanofluid consistently exhibits a thinner boundary layer and a steeper velocity gradient compared to the mono nanofluid. This behavior is attributed to the synergistic effect of alumina and silica nanoparticles, which enhances both momentum and thermal diffusivities, thereby intensifying velocity near the wall region.

Figure 3 highlights the role of thermal dispersion on the velocity distribution. As the dispersion parameter increases, the velocity profile rises near the surface, indicating that enhanced thermal dispersion promotes a more efficient distribution of thermal energy within the fluid, which in turn accelerates fluid motion close to the wall. The effect is more pronounced in hybrid nanofluids, as the combined nanoparticles facilitate stronger thermal conductivity and convective interactions than mono nanofluids.

Overall, Figures 2 and 3 show that hybrid nanofluids outperform mono nanofluids in boundary layer control and flow enhancement. This improvement occurs under the combined effects of suction, injection, and thermal dispersion. This indicates their superior potential in applications requiring efficient thermal management and convective heat transfer augmentation.

Figure 2. Mono nanofluid / hybrid nanofluid impact on velocity profile with suction/injection effect

Figure 3. Mono nanofluid / hybrid nanofluid impact on velocity profile with dispersion effect.

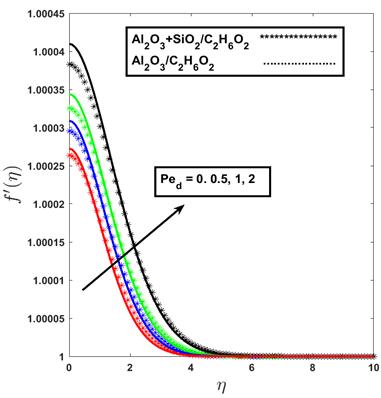

Figure 4 illustrates the effect of

the Biot number on the surface heat transfer rate for varying values of the mixed convection

parameter ![]() . When

. When ![]() , the flow corresponds to pure forced

convection, while increasing values of

, the flow corresponds to pure forced

convection, while increasing values of ![]() reflect

a transition toward mixed and ultimately free convection, where buoyancy

effects dominate. As the Biot number increases from 0.5 to 1.5, the heat

transfer rate (represented through the Nusselt number) rises steadily. This

enhancement is attributed to the stronger convective heat exchange at the

fluid–solid interface, since a higher Biot number signifies more efficient

energy transfer from the surface into the fluid medium.

reflect

a transition toward mixed and ultimately free convection, where buoyancy

effects dominate. As the Biot number increases from 0.5 to 1.5, the heat

transfer rate (represented through the Nusselt number) rises steadily. This

enhancement is attributed to the stronger convective heat exchange at the

fluid–solid interface, since a higher Biot number signifies more efficient

energy transfer from the surface into the fluid medium.

Across all values of ![]() , the hybrid nanofluid demonstrates a

consistently higher heat transfer rate compared to the mono nanofluid and the

base fluid. This superior performance results from the synergistic thermal

properties of alumina and silica nanoparticles. They collectively improve

thermal conductivity, enhance energy transport mechanisms, and reduce thermal

boundary layer thickness. The improvement becomes especially prominent under

stronger buoyancy-driven conditions (higher

, the hybrid nanofluid demonstrates a

consistently higher heat transfer rate compared to the mono nanofluid and the

base fluid. This superior performance results from the synergistic thermal

properties of alumina and silica nanoparticles. They collectively improve

thermal conductivity, enhance energy transport mechanisms, and reduce thermal

boundary layer thickness. The improvement becomes especially prominent under

stronger buoyancy-driven conditions (higher ![]() ).

Here, the interplay between thermal dispersion and convection further augments

the heat transfer. This

establishes their suitability for thermal systems where both conduction and

convection mechanisms are critical.

).

Here, the interplay between thermal dispersion and convection further augments

the heat transfer. This

establishes their suitability for thermal systems where both conduction and

convection mechanisms are critical.

Figure 4. Effect of mono nanofluid and hybrid nanofluid on heat transfer rate with the variation of biot number

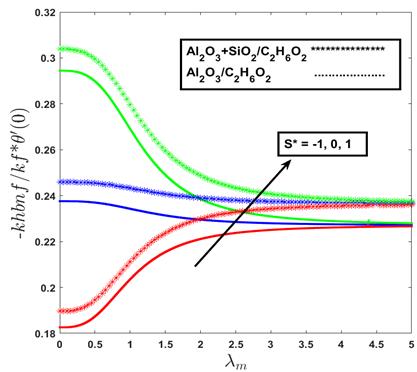

Figure 5 shows that lower thermal

dispersion corresponds to higher heat transfer rates, as it maintains a steeper

surface temperature gradient. In contrast, stronger dispersion redistributes

thermal energy within the fluid, smoothing the temperature profile and

weakening heat transfer. When the mixed convection parameter (![]() ) lies between 0 and 1, corresponding to

the transition from forced to mixed convection, the heat transfer rate remains

relatively modest. However, as

) lies between 0 and 1, corresponding to

the transition from forced to mixed convection, the heat transfer rate remains

relatively modest. However, as ![]() exceeds 1,

entering the free convection–dominated regime, the heat transfer rate increases

significantly. This enhancement is most pronounced for the hybrid nanofluid. It

underscores its greater sensitivity to buoyancy-driven mechanisms and its

superior thermal transport capability compared to the mono nanofluid.

exceeds 1,

entering the free convection–dominated regime, the heat transfer rate increases

significantly. This enhancement is most pronounced for the hybrid nanofluid. It

underscores its greater sensitivity to buoyancy-driven mechanisms and its

superior thermal transport capability compared to the mono nanofluid.

Figure 5. Effect of mono nanofluid and hybrid nanofluid on heat transfer rate with the variation of dispersion parameter

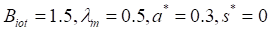

Figure 6 highlights the influence

of the suction/injection parameter ![]() . Suction

. Suction ![]() enhances heat transfer by reducing the

thermal boundary layer thickness, while injection

enhances heat transfer by reducing the

thermal boundary layer thickness, while injection ![]() weakens

heat transfer by supplying additional fluid at the surface. The no mass

transfer case

weakens

heat transfer by supplying additional fluid at the surface. The no mass

transfer case ![]() shows only a minor decrease.

These effects are strongest in the forced convection region

shows only a minor decrease.

These effects are strongest in the forced convection region ![]() , diminish progressively in the mixed

convection regime, and become negligible when buoyancy

, diminish progressively in the mixed

convection regime, and become negligible when buoyancy ![]() . The hybrid nanofluid consistently

benefits more from suction. It reflects its enhanced momentum and thermal diffusivity

due to the combined effects of alumina and silica nanoparticles.

. The hybrid nanofluid consistently

benefits more from suction. It reflects its enhanced momentum and thermal diffusivity

due to the combined effects of alumina and silica nanoparticles.

Figure 6. Effect of mono nanofluid and hybrid nanofluid on heat transfer rate with the variation of suction/injection parameter

So, thermal dispersion and suction/injection strongly influence heat transfer behavior in the forced and mixed convection regimes, while in free convection conditions, buoyancy effects dominate. The hybrid nanofluid demonstrates superior adaptability and higher thermal performance across all regimes.

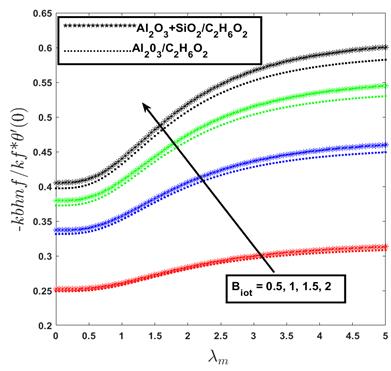

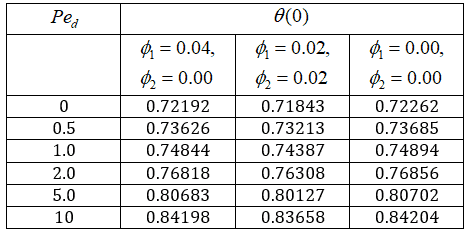

To further illustrate the

significance of thermal dispersion in hybrid nanofluid transport, Table 6

presents the variation of surface temperature distribution ![]() with respect to the pore dependent Peclet

number

with respect to the pore dependent Peclet

number ![]() . The data include results for

the mono nanofluid, hybrid nanofluid, and the regular base fluid. The data

clearly indicate that

. The data include results for

the mono nanofluid, hybrid nanofluid, and the regular base fluid. The data

clearly indicate that ![]() increases monotonically

with

increases monotonically

with ![]() ,

reflecting stronger dispersion-induced thermal mixing. Among the three cases,

the hybrid nanofluid consistently shows slightly lower surface temperature

values than the mono nanofluid and base fluid. This implies more efficient heat

removal due to the combined nanoparticle effect. The differences become more

pronounced at higher Peclet numbers, emphasizing the hybrid suspension’s

superior capacity to manage heat transport under enhanced dispersion

conditions. This behavior highlights the necessity of incorporating dispersion

effects in analyzing mixed convection of hybrid nanofluids over different porous

geometries. This aspect is the central focus of the present work.

,

reflecting stronger dispersion-induced thermal mixing. Among the three cases,

the hybrid nanofluid consistently shows slightly lower surface temperature

values than the mono nanofluid and base fluid. This implies more efficient heat

removal due to the combined nanoparticle effect. The differences become more

pronounced at higher Peclet numbers, emphasizing the hybrid suspension’s

superior capacity to manage heat transport under enhanced dispersion

conditions. This behavior highlights the necessity of incorporating dispersion

effects in analyzing mixed convection of hybrid nanofluids over different porous

geometries. This aspect is the central focus of the present work.

Table 6. Dispersion effect on  for the the

values

for the the

values

5. Conclusion

This work presented a numerical investigation of hybrid nanofluid mixed convection over a horizontal cone with the inclusion of thermal dispersion effects. Alumina–silica nanoparticles suspended in ethylene glycol were considered, and the governing equations were solved through similarity transformations and the Bvp4c method. The analysis establishes that hybrid nanofluids provide distinct thermal and flow advantages compared to mono nanofluids and the pure base fluid. The combined presence of multiple nanoparticles improved transport efficiency in porous geometries, offering performance benefits relevant to engineering systems. Key controlling parameters, such as the Biot number, dispersion strength, and suction/injection conditions, were shown to strongly influence system response, underscoring the complexity of heat and momentum transfer in such configurations.

Overall, the outcomes emphasize the relevance of hybrid nanofluids in enhancing convection-driven energy transport for practical applications in energy harvesting, cooling technologies, and compact heat exchangers.

5.1. Future Work

Building on this study, future research can address temperature-dependent thermophysical properties and extend the model to non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluids. External influences such as magnetic or electric fields, thermal radiation, or chemical reactions could also be incorporated to capture more realistic operating conditions. Entropy generation and second-law analyses may provide deeper insights into system efficiency. Furthermore, experimental validation of the theoretical findings would be essential to translate these results into practical design strategies for advanced thermal management technologies.

References

[1] M. F. Amran, N. M. Anas, and M. Z. Abdullah, "Effects of Prandtl number, geometry, and orientation on mixed convection heat transfer: A review," Processes, vol. 12, no. 12, p. 2749, 2024. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12122749 View Article

[2] N. Thongjub and V. Ngamaramvaranggul, "Simulation of die-swell flow for Oldroyd-B model with feedback semi-implicit Taylor Galerkin finite element method," KMUTNB International Journal of Applied Science Technology, vol. 8(1), pp. 55-63, 2015. View Article

[3] R. I. Tanner, "A theory of die-swell," Journal of Polymer Science Part A-2: Polymer Physics, vol. 8(12), pp. 2067-2078, 1970. View Article

[4] S. Richardson, "A stick-slip problem related to the motion of a free jet at low Reynolds numbers," Proc. Camb. Phil. Soc., vol. 67, pp. 477-489, 1970. View Article

[5] J. Thiry, F. Krier, and B. Evrard, "A review of pharmaceutical extrusion: Critical process parameters and scaling-up," International Journal of Pharmaceutics, vol. 479, pp. 227-240, 2015. View Article

[6] N. Thongjub and V. Ngamaramvaranggul, "Simulation of die-swell flow for wet powder mass extrusion in pharmaceutical process," Applied Science and Engineering Progress, vol. 13(4), pp. 354-361, 2020. View Article

[7] J. Vlachopoulos, M. Horie, and S. Lidorikis, "An evaluation of expressions predicting die swell," Trans. Soc. Rheol., vol. 16(4), pp. 669-685, 1972. View Article

[8] M. Okabe, "Fundamental theory of the semi- radial singularity mapping with applications to fracture mechanics," Comp. Meth. App. Mech. Eng., vol. 26, pp. 53-73, 1981. View Article

[9] B. Caswell and R. I. Tanner, "Wirecoating die design using finite element methods," Polym. Eng. Sci., vol. 18(5), pp. 416-421, 1978. View Article

[10] P. Wapperom and O. Hassager, "Numerical simulation of wire-coating: The influence of temperature boundary conditions," Polym. Eng. Sci., vol. 39(10), pp. 2007-2018, 1999. View Article

[11] E. Mitsoulis, "Finite element analysis of wire coating," Polym. Eng. Sci., vol. 26(2), pp. 171-186, 1986. View Article

[12] E. Mitsoulis, R. Wagner and F. L. Heng, "Numerical simulation of wire-coating low-density polyethylene: Theory and experiments," Polym. Eng. Sci., vol. 28(5), pp. 291-310, 1988. View Article

[13] I. Mutlu, P. Townsend and M. F. Webster, "Simulation of cable-coating viscoelastic flows with coupled and decoupled schemes," J. Non-Newtonian Fluid Mech., vol. 74, pp. 1-23, 1998. View Article

[14] H. Matallah, P. Townsend and M. F. Webster, "Viscoelastic computations of polymeric wire-coating flows," Int. J. Numer. Meth. Heat & Fluid Flow, vol. 12(4), pp. 404-433, 2002. View Article

[15] H. Matallah, P. Townsend and M. F. Webster, "Viscoelastic multi-mode simulations of wire-coating," J. Non-Newtonian Fluid Mech., vol. 90, pp. 217-241, 2000. View Article

[16] N. Phan-Thien, "Influence of wall slip on extrudate swell: A boundary element investigration," J. non-Newtonian Fluid Mech., vol. 26, pp. 327-340, 1988. View Article

[17] H. Baloch, H. Matallah, V. Ngamaramvaranggul and M. F. Webster, "Simulation of pressure- and tube- tooling wire-coating flows through distributed computation," Int. J. Numer. Meth. Heat & Fluid Flow, vol. 12, pp. 458-493, 2002. View Article

[18] V. Ngamaramvaranggul and S. Thenissara, "The contraction point for Phan-Thien/Tanner model of tube-tooling wire-coating flow," International journal of Physical and Mathematical Science, vol. 4(4), pp. 627-631, 2010.

[19] N. Thongjub, B. Puangkird, and V. Ngamaramvaranggul, "Simulation of slip effect with 4:1 contraction flow for Oldroyd-B fluid," Asian International Journal of Science and Technology in Production and Manufacturing Engineering, vol. 6(3), pp. 19-28, 2013.

[20] R.Y. Chang and W.L. Yang, "Numerical simulation of non-isothermal extrudate swell at high extrusion rates," J. Non-Newtonian Fluid Mech., vol. 51, pp. 1-19, 1994. View Article

[21] G. Barakos and E. Mitsoulis, "Non-isothermal viscoelastic simulations of extrusion through dies and prediction of the bending phenomenon," J. Non-Newtonian Fluid Mech., vol. 62, pp. 55-79, 1996. View Article

[22] V. Anand, "Effect of slip on heat transfer and entropy generation characteristics of simplified Phan-Thien-Tanner fluids with viscous dissipation under uniform heat flux boundary conditions: Exponential formulation," Applied Thermal Engineering, vol. 98, pp. 455-473, 2016. View Article

[23] D. Bhukta, S. R. Mishra, and M. M. Hoque, "Numerical simulation of heat transfer effect on oldroyd 8-constant fluid with wire coating analysis," Int. J. Engineering Science and Technology. vol. 19, pp. 1910-1918, 2016. View Article

[24] A. Mavi, T. Chinyoka, and A. Gill, "Modelling and analysis of viscoelastic and nanofluid effects on the heat transfer characteristics in a double-pipe counter-flow heat exchanger," Applied Sciences, vol. 12(11), 5475, pp. 1-33, 2022. View Article

[25] V. Ngamaramvaranggul and M. F. Webster, "Simulation of pressure-tooling wire-coating flows with Phan-Thien/Tanner models," Int. J. Num. Meth. Fluids., vol. 38(7), pp .677-710, 2002. View Article